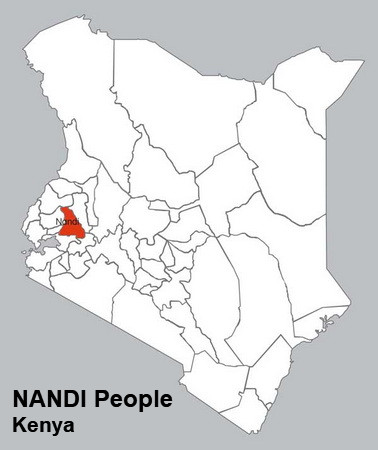

The Nandi are part of the Kalenjin, a Nilotic tribe living in East Africa. The Nandi ethnic group live with close association and relation with the Kipsigis tribe. They traditionally have lived and still form the majority in the highland areas of the former Rift Valley Province of Kenya, in what is today Nandi County. They speak the Nandi dialect of the Kalenjin language.

The Nandi is a sub community of the Kalenjin ethnic group. They referred to themselves as 'Chemwalindet' or 'Chemwal' before adopting the name Nandi in the mid 19th century. Due to the fertile soils and abundant rainfall in Nandi County, the Nandi have traditionally practiced agriculture and livestock keeping.

The Nandi live in Nandi County, Uasin-Gishu County, Trans-Nzoia County, Nakuru County and parts of Narok County.

Before the mid-19th century, the Nandi referred to themselves as Chemwalindet (pl. Chemwalin) or Chemwal (pl. Chemwalek) while other Kalenjin-speaking communities referred to the Nandi as Chemngal. It is unclear where the terms originated from, though in early writings the latter term was associated with ngaal which means camel in Turkana and suggestions made that the name could be an "...allusion to the borrowing, direct or indirect of the rite of circumcision from camel riding Muslims". Later sources do not make similar suggestions or references to this position.

The name Nandi came into use after the mid-19th century and more so after the defeat of the Uasin Gishu and the routing of the Swahili and Arab traders. The name is thought to derive from the similarity of the rapaciousness of the warriors of the mid-1800s to the habits of the voracious cormorant which is known as mnandi in Kiswahili.

They speak nandi, a Kalenjin dialect. Their dialect of Kalenjin is classified in the Nilotic branch of the Nilo-Saharan language family; they are distinct from the Nandi of Congo (Kinshasa), whose language is classified as Niger-Congo.

The people are divided among 17 patrilineal and exogamous clans dispersed throughout Nandi territory.

Nandi society was traditionally egalitarian.

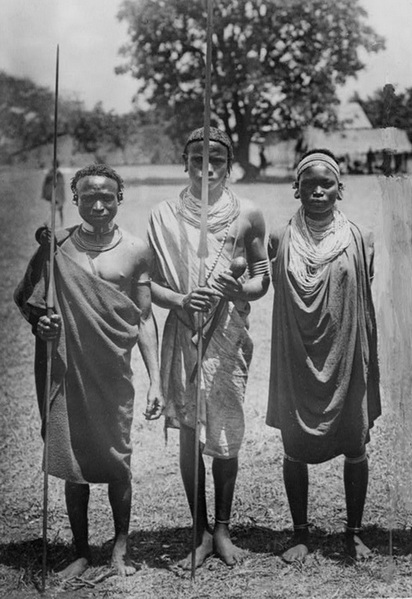

The family was the smallest social unit in the Nandi community, which was traditionally divided into seventeen clans. The community had a cyclic age set system to which all male members belonged from birth. They had seven age grades, covering 15 years. Men advanced to warriorhood after circumcision, then became elders, and were later incorporated into the council elders with political and judicial authority. Men provided food and protection for the family, while women took care of children and all household chores. Children, on the other hand, helped their parents until they were initiated into adulthood, when they took up more responsibilities.

The family was the basic political unit among the Nandi. A collection of between 20 to 100 homesteads formed a koret. A dozen or more koret formed a pororiet, a larger political unit that produced men to join military camps.

The pororiet was regulated by the council of elders, where leaders from every koret attended. Leaders assumed these positions by virtue of their social status, wealth and personality, and settled disputes through consensus.

The Nandi also had a spiritual and military leader called Orkoiyot, who made security and war decisions.

The most important traditional social groups are the age sets, to one of which every male belongs from birth. The Nandi age grade system is of the cyclical type, with seven named grades covering approximately 15 years each, a single full cycle being 105 years. Men advance through the warrior grades and, upon entering the grade of elder, hold political and judicial authority. No political authority transcends this local council of elders.

When a child was born, a 'spirit' name would be decided upon and given to it after four days. That name would be related to a particular ancestor. After three months, when weaning, the child would be given a personal name replacing that of their ancestor.

They traditionally practice circumcision of both sexes, although female circumcision is fast fading as a rite of initiation into adulthood.

Boys' circumcision festivals took place about every seven and a half years, and boys circumcised at the same time are considered to belong to the same age set; like other Nilotic groups, these age sets (called ibinda, pl. ibinweek) were given names from a limited fixed cycle.

Each age set is further subdivided into a subset (siritieet, pl. siritoiik). About four years after this festival, the previous generation officially handed over defense of the country to the newly circumcised youths.Girls' circumcision, excising the clitoris, took place in preparation for marriage.

The Nandi conducted a circumcision ceremony every seven and a half years for both boys and girls. Prior to the operation, boy initiates wore girls' garments and vice versa, in an interesting ritual inversion.

After circumcision all initiates went into seclusion, where they were taught their responsibilities. Girls in seclusion wore leather hoods while boys wore grass masks. Boys circumcised at the same time made an age set.

Female circumcision is no longer permitted in the country, hence alternative initiation practices are now encouraged.

General polygyny is the rule, with substantial bride-price in livestock expected.

Traditionally, marriages were arranged and bride-wealth was paid to the bride's family. Once married, the man provided a house and a piece of land for his wife or wives to cultivate. Customarily, barrenness was the only reason for a divorce.

The Nandi believed in a supernatural being, Asis (sun), to whom they presented prayers every morning and evening. They also had special prayers conducted under sacred trees, especially after harvesting to offer thanksgiving. They would slaughter a white sheep whose intestines were read by the elders to establish if there were any impending calamities. They also wore charms on their bodies for protection against evil spirits and sicknesses.

Many of the cultural practices of the Nandi are still embraced today, but have been influenced by the changes in society. The heritage and culture of the Nandi community, along with the more than 44 communities in Kenya, continues to fascinate and inspire. The National Museums of Kenya invites everyone to celebrate the intangible cultural heritage of all communities which makes up this great nation.

They traditionally worshiped a supreme deity, Asis (literally "Sun"), as well as venerating the spirits of ancestors. Their land is divided into six "counties" (emet): Wareng in the north, Mosop in the east, Soiin/Pelkut in the south, Aldai and Chesumei in the west, and Em-gwen in the center.

The Orkoiyot, or medicine man, was traditionally acknowledged as an overall leader. The Orgoiyot led not only in spiritual matters but also during wars, as evidenced during the war between the British colonials building the railway and the Nandi warriors.

The leader at that time was Koitalel Arap Samoei who was killed by Richard Meinertzhagen, a British soldier. In pre-colonial times, they also enjoyed a fearsome reputation as fighters; Arab slave-traders and ivory-traders took care to avoid the area, and the few that dared attempt to traverse it were killed.

The Nandi have had a well structured 'political' system revolving around what might be referred to at the Nandi Bororiet. No other Kalenjin community organised themselves in the Bororiet (pl. bororiosiek) system. The Nandi political life was ordered around 'bororiet' which is distinctly different from oreet (clan) but is probably an expanded form of the advanced order of the 'kokwet' or village system.

Have to consider bororiet as a form of a political party. For example, if one's family lived in one bororiet but was haunted by repetitive deaths that pointed to a curse, a ceremony reminiscent of 'Kap Kiyai' was performed to allow the family to change their bororiet by 'crossing a river' in the context of 'ma yaitoos miat aino' which literally means that death does not cross a river (body of water).

This elaborate ceremony was called 'raret' (rar means trim or cut off). If you find a family with a name Kirorei then you probably have a family case of bororiet change which came about as a result of 'rareet' (chopping off).

People changed bororiet as a result of migration to another koreet, emeet (region). This seems common for some bororiosiek and not others, however. For example an individual who moved to Kabooch could retain the unique identity, leading perhaps derogatively, to the reference of skin rashes that develop on kids heads as 'Kaboochek'.

Another instance of change of bororiet is a shameful perhaps spiteful defection 'martaet' which means somebody deserts his bororiet for another. This brings to mind names such as Kimarta. Within each Bororiet were siritoik or sub-bororiet.

Female-female marriages within the Nandi culture have been reported, although it is unclear if they are still practiced, and only about three percent of Nandi marriages are female-female. Female-female marriages are a socially-approved way for a woman to take over the social and economic roles of a husband and father.

They were allowed only in cases where a woman either had no children of her own, had daughters only (one of them could be "retained" at home) or her daughter(s) had married off.

The system was practiced "to keep the fire"—in other words, to sustain the family lineage, or patriline, and was a way to work around the problem of infertility or a lack of male heirs.

A woman who married another woman for this purpose had to undergo an "inversion" ceremony to "change" into a man. This biological woman, now socially male, became a "husband" to a younger female and a "father" to the younger woman's children, and had to provide a bride price to her wife's family.

She was expected to renounce her female duties (such as housework), and take on the obligations of a husband; additionally, she was allowed the social privileges accorded to men, such as attending the private male circumcision ceremonies.

No sexual relations were permitted between the female husband and her new wife (nor between the female husband and her old husband); rather, the female husband chose a male consort for the new wife so she will be able to bear children.

The wife's children considered the female husband to be their father, not the biological father, because she (or "he") was the socially designated father.

The main issues/problems concerning population and development in the district include the following are: - Integration of population issues into development planning. The issue here is weak integration of population concerns into development planning due to inadequate finances to facilitate the integration process, insufficient facilities and equipment for the District Planning Unit and training of personnel involved in the integration process.

The Nandi of Kenya are primarily intensive cultivators; their major crops are millet, corn (maize), and sweet potatoes (yams). Cattle serve many functions, providing food and bride-price payments and holding great ritual significance.

The Kalenjin are essentially semipastoralists. Cattle herding is thought to be ancient among them. Although the real economic importance of herding is slight compared to that of cultivation among many Kalenjin groups, they almost all display a cultural emphasis on and an emotional commitment to pastoralism.

Cattle numbers have waxed and waned; however, cattle/people ratios of 5:1 or greater (typical of peoples among whom herding is economically dominant) have been recorded only for the pastoral Pokot.

In their late-nineteenth-century heyday of pastoralism, the Nandi and the Kipsigis approached this ratio; 1-3:1 is more typical of the Kalenjin, and in some communities the ratio is even lower than 1:1.

The staple crop was eleusine, but maize replaced it during the colonial era. Other subsistence crops include beans, pumpkins, cabbages, and other vegetables as well as sweet and European potatoes and small amounts of sorghum.

Sheep, goats, and chickens are kept. Iron hoes were traditionally used to till; today plows pulled by oxen or rented tractors are more common. The importance of cash crops varies with land availability, soil type, and other factors; among the Nandi and the Kipsigis, it is considerable.

Surplus maize, milk, and tea are the major cash crops. Kalenjin farms on the Uasin Gishu plateau also grow wheat and pyrethrum.

In most communities there are a few wage workers and full-time business persons (shopkeepers, tailors, carpenters, bicycle repairmen, tractor owners) with local clienteles. It is common for young married men to be part-time entrepreneurs. Historically, women could brew and sell beer; this became illegal in the early 1980s. Some men work outside their communities, but labor migration is less common than elsewhere in western Kenya.

Traditionally, there were no full-time craft specialists. Most objects were manufactured by their users. The blacksmith's art was passed down in families in particular localities, and some women specialized in pottery.

Traditionally, women conducted a trade of small stock for grain between pastoral-emphasis and cultivation-emphasis (often non-Kalenjin) communities. Regular local markets were rare prior to the colonial era. Today large towns and district centers have regular markets, and women occasionally sell vegetables in sublocation centers.

There was little traditional division of labor except by age and sex. Men cleared land for cultivation, and there is evidence that married men and women cooperated in the rest of the cultivation process. Husbands and wives did not (except during a limited historical period)—and do not—typically cultivate separately, other than the wife's vegetable garden. Today women do more cultivation if their husbands are engaged in small-scale business activities.

Children herded cattle close to the homestead, as well as sheep and goats; warriors (young initiated men) herded cattle in distant pastures. Women and girls milked, cooked, and supplied water and firewood. Today boys are the main cowherds, and girls are largely responsible for infant care. The children's role in domestic labor is extremely important, even though most children now attend school.

In Nandi, individual title to land replaced a system in which land was plentiful, all who lived in a community had the right to cultivate it, and a man could move with his family to any locality in which he had a sponsor.

Land prepared for cultivation, and used regularly, was viewed as belonging to the family that used it, and inherited from mother to son. The tenure systems of other Kalenjin were mainly similar.

The Kerio Valley groups cultivated on ridges and at the foot of ridges, using irrigation furrows that required collective labor to maintain.

This labor was provided by clan segments, which cleared and held land collectively, although cultivation rights in developed fields were held by individual families.

Sources