The Sukuma are a Bantu ethnic group from the southeastern African Great Lakes region.

They are the largest ethnic group in Tanzania, with an estimated 10 million members or 16 percent of the country's total population.

Sukuma means "north" and refers to "people of the north." The Sukuma refer to themselves as Basukuma (plural) and Nsukuma (singular).

They speak Sukuma, which belongs to the Bantu branch of the Niger-Congo family

The Nyamwezi and Sukuma are two closely related ethnic groups that live principally in the region to the south of Lake Victoria in west-central Tanzania. When using ethnic names, they describe themselves as "Banyamwezi" (sing. Munyamwezi) and "Basukuma" (sing. Musukuma) respectively; they refer to their home areas as "Bunyamwezi" or "Unyamwezi," and as "Busukuma." The term "Sukumaland" is sometimes used for the Sukuma area. The name "Sukuma" literally means "north," but it has become a term of ethnic identification.

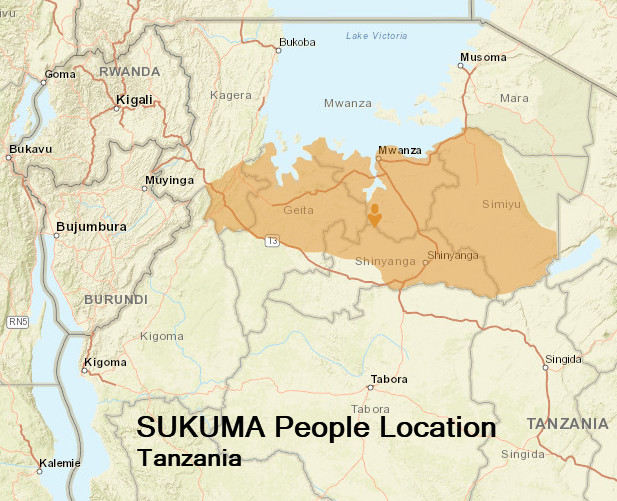

The Sukuma live in northwestern Tanzania on or near the southern shores of Lake Victoria, and various areas of the administrative districts of the Mwanza, southwestern tip of Mara Region, Simiyu Region and Shinyanga Region. The northern area of their residence is in the Serengeti Plain. Sukuma families have migrated southward, into the Rukwa Region and Katavi Region, encroaching on the territory of the Pimbwe. These Sukuma have settled outside Pimbwe villages.

The Sukuma land is mostly a flat, scrubless savannah plain between 910 and 1,220 metres (3,000 and 4,000 ft) elevation. Twenty to forty inches (51 to 102 cm) of rain fall from November to March. High temperatures range from 26 to 32 °C (79 to 90 °F) while lows at night seldom drop below 15 °C (59 °F). The population is spread out among small farm plots and sparse vegetation.

Estimates of the modern population are difficult to make because Tanzanian censuses no longer record the ethnic affiliation of enumerated local populations. According to Tanzanian newspaper reports based on official estimates, there were 1 to 1.5 million Nyamwezi and between 3 and 3.5 million Sukuma in 1989. Census figures for 1978 show a wide range of population densities, from 73.3 per square kilometer in the Mwanza Region to 10.7 per square kilometer in the Tabora Region. Since then, population growth in Tanzania generally has been about 2.8 percent per annum, but densities have also been influenced by population movement.

Although sometimes classed as two closely related languages, Nyamwezi and Sukuma are probably best considered as a single Bantu language with several mutually intelligible dialects. These features include a seven-vowel system, use of tone, true negative tenses, class prefixes to indicate size, and the restriction of double prefixes to determined situations. In addition to their own dialect, most people today also speak Swahili.

In the nineteenth century large compact villages were common, especially among the Nyamwezi. As the country became peaceful, people moved out to build in their own fields. The dispersal of settlement continued until the first years of independence, and villages passed through phases of expansion and decline as soils became worn out and the age structure of their populations changed. In the mid-1970s new compact villages, ideally of 250 households, were established by decree throughout this and other parts of Tanzania.

Each household had a 0.4-hectare plot within the village on which to build and cultivate, and families also had access to fields in surrounding land.

he 0.4-hectare plots were commonly arranged in blocks of ten between new village streets. This policy has since been relaxed, and some settlements are said to be disbanding.

Agriculture and cattle keeping are the chief economic activities. Most families grow food for themselves and attempt to produce some surplus for the market. Maize, sorghum, and rice are the main food crops sold, and cotton and tobacco are produced in substantial quantities. Other crops include groundnuts, beans, cassava, and some vegetables and fruits. The main cattle owners are Sukuma. Some families own very large herds of a thousand head or more, but smaller herds are more usual. Small stock are also raised. Most families still use hoes, but plows pulled by oxen are quite common. Some richer people own tractors that they hire out to others, in addition to using them to cultivate large areas for themselves.

Traditional crafts include building, ironwork, pottery, basketry, drum making, and stool carving. These crafts are usually part-time occupations, and some have declined as foreign goods have been imported. Bow and arrow making has enjoyed a resurgence with the rise of Sungusungu (see "Sociopolitical Organization"). Some carpenters make Western-type chairs and other furniture, and some men work as sewing-machine operators in local shops.

Local caravans down to the coast ceased in colonial times, but people continued to go as porters and migrant laborers. Shops were largely owned by Asians and Arabs, but after independence local shopkeepers became common in the villages and towns. Private trade was discouraged by the state for many years, and cooperative shops and state trading agencies were established. The private sector has persisted, however, and there are many successful businesses, especially among the Sukuma.

There is a strong sexual division of labor. In general, men do shorter, heavy tasks, and women do more repetitive chores. Cattle are mainly men's concern, as are ironworking and machine sewing. Only men hunt. Pottery is women's work. Some urgent tasks, such as harvesting, are done by both sexes. Most diviners are men. The state has been keen to draw women into politics, but only moderate progress has been made.

Under the chiefs, land could be acquired in several ways. A villager might clear new land or obtain cleared land from a village headman. He might also inherit land with agreement from the headman. The chief was said to be "owner" of the land; this meant that those who held it were his subjects, and that the prosperity of the chiefdom depended on him and his ancestors. There was some variation in the degree of control that chiefs and headmen exercised over land. Fields could not customarily be sold, but those who had cleared land could often lend it to others and pass it on to heirs. In the 1960s, once chieftainship was abolished, land started to be sold, but this was stemmed by government. Later, land was defined as belonging to a village as the agent of the state. Villagers were allocated land for their own use, and some land was retained for communal production. Some villagers are now returning to live on their former holdings.

The main kin groups in the area were those vested with political office. Since independence, their importance has diminished, although they still provide valuable personal networks for their members. The groups were mainly based on descent from former chiefs and other officeholders. Officeholders were also a focus for sets of relatives who clustered around them. Some Sukuma classify themselves into "clans" defined in terms of their members' chiefdom of origin. For most people, kinship is important mainly for interpersonal relations. A person's kin are widely dispersed, and villages are not typically kinship units. The main structural elements of the kinship system are oppositions between male and female, senior and junior, and proximal and alternate generations. One notable feature of behavior between kin is the division between those with whom one is familiar or jokes, and those whom one "respects" or avoids. This runs partly along generation lines and is at its strongest between affines. Sexual difference is also a factor. Thus, brothers-inlaw joke with each other, and there is avoidance between a man and his daughter-in-law and mother-in-law. Known kin should not marry. A main determinant of people's status vis-àvis their kin is the form of their parents' marriage (see "Marriage").

Some features of the kinship system are reflected in the Iroquoian kinship terminology used by the Nyamwezi, which distinguishes kin from affines, mother's kin from father's kin in proximal generations, cross cousins from siblings and ortho-cousins, and proximal from alternate generations. Parental and great-grandparental generations are merged, as are those of grandparents and great-great-grandparents. Similar patterns are followed in the terms for junior generations. Some puzzling Crow features (father's sister's son = father) have been reported for the traditional Sukuma terminology.

Local forms of marriage fall into two main classes, marriage with bride-wealth and marriage without bride-wealth. In bride-wealth marriage, a husband customarily acquires full rights over the children his wife bears. He should receive bride-wealth for his daughters and provide it for his sons, and his children should inherit from him. He also has customary rights to compensation for his wife's adultery. Adultery is still an offense if no bride-wealth has been given, but compensation is not customarily paid. Rights over children of non-bride-wealth unions are mainly vested in maternal kin, unless the father makes redemption payments for them. These payments are larger for a daughter than for a son. The verb kukwa is used for these payments and also for paying bride-wealth. Bride-wealth marriage is more common in prosperous areas and times. The verb kutola is commonly used for both forms of marriage. A man "marries," and a woman "is married." Residence at marriage varies but is increasingly neolocal. Patrivirilocal residence is most common when bride-wealth is paid, but sons often move away eventually. Bride-service with initial uxorilocal residence is reported to have existed formerly among the Sukuma. Polygyny is a common male ambition, but polygynous marriages are relatively unstable. Many men have been polygynous, but, with the main exception of chiefs in the past, older men are less polygynous than those in their forties. More generally, divorce is frequent. Women's first marriages in which bride-wealth has been paid are the most stable.

Before the 1970s, homesteads sometimes contained a dozen or more people, although most were smaller. They commonly consisted of a man and his wife or wives, their resident children, and perhaps the spouse and the children of one or more of the resident children. Other close relatives of the head of the homestead might also be present. Homesteads were the largest units in which members of one sex regularly ate together. They contained one or more households that were distinct food-producing and child-rearing units. The household was the basic economic unit and the husband-wife relation was its key element. This has been reinforced in new compact village where each 0.4-hectare plot is assigned to a familia (modern Swahili) based on a couple and their children. Neighboring households collaborate in a wide range of activities.

Questions of inheritance are usually resolved within the families concerned. Customarily only sons of bride-wealth marriages, or redeemed sons, inherit the main forms of wealth. Such heirs should look after the needs of daughters. Sometimes one son looks after an inheritance for all his siblings. Unredeemed children are in a weak position; they may fail to inherit either from their father or from their mother's kin, whose own children may take precedence.

Socialization takes place largely within the family and village. Ceremonies within a few days of birth symbolize a baby's future as a male or female member of society. Girls especially learn their gender roles quite early, through participation in household tasks. Boys help in herding and other work but have more free time than do girls during their teens. There are no formal age groups or ceremonies of initiation into adulthood. Primary schooling is now compulsory, but parents sometimes keep children from school if their labor is required. Training in citizenship is part of the school curriculum.

Before independence the main forms of political organization were the chiefdoms and the villages. Neighbors, and also kin, collaborate in many activities, and there are several ritual and secular associations and societies. Since independence, as part of the Republic of Tanzania, the area inhabited by the Nyamwezi and the Sukuma has been subject to its laws and constitution. It falls administratively within Mwanza, Shinyanga, and Tabora regions, which contain several administrative districts. These districts are segmented into divisions, which, in turn, contain wards, within which there are officially constituted villages. There are governmental and party officials at each level, and a series of elected committees. Since 1973, villages have been the basic unit of organization, although, within them, ten-house groups are recognized. In the early 1980s a new grass-roots village-security organization—Sungusungu or Busalama—emerged, and it has spread to all parts of the area. All able-bodied village men belong to the local Sungusungu group, and there is sometimes a women's wing. Conflicts have occurred between the Revolutionary party (CCM) and Sungusungu, but there has also been some cooperation between them, and the groups are now legally recognized. Each village has its own group, but there is also some intervillage collaboration. Single-party rule is due to end, and multiparty elections are planned in the mid-1990s.

There are official district-level courts, and below these there are primary courts. These administer national and some customary law. Neighbors' courts dealt with many disputes in the past, but nowadays Sungusungu groups hear cases. Their function is to maintain village security against cattle thieves and other enemies, including witches in some areas. Members are armed with bows and arrows, which have proved to be effective weapons for them, and with whistles for sounding alarms.

Since World War I, the area has been relatively peaceful. The independence struggle was active but mainly nonviolent. Class conflict is not yet strongly developed, although there are substantial differences in wealth in some areas. Initial official reactions to Sungusungu were mainly negative, but the groups received qualified support from Julius Nyerere and some other leading Tanzanian figures. Government has since tried to control the groups and encourage their development elsewhere, but there are signs that enthusiasm for the system is declining among villagers themselves.

With the main exceptions of the villages around Tabora and of areas around some Christian missions, neither Islam nor Christianity has flourished strongly among villagers. Religion in the area, like society itself, is accretive rather than exclusive.

Beliefs in a High God are widely held but involve no special cult. Ancestor worship is the main element in the religious complex. Chiefs' ancestors are thought to influence the lives of the inhabitants of their domains, but ordinary ancestors only affect their own descendants. Belief in witchcraft is widespread and strong.

In addition to the High God and the ancestors, some nonancestral spirits are believed to influence some people's lives. Spirit-possession societies, such as the Baswezi, deal with such attacks and recruit the victims into membership.

As a link between belief and action, the diviner ( mfumu ) is a key figure in religious life; diviners interpret the belief system for individuals and groups. They decide which forces are active and help people to deal with them. Although it is not strictly an hereditary art, people often take up divination when a misfortune is diagnosed as having been induced by a diviner ancestor who wishes them to do so. There are often several diviners in a village, but only one or two are likely to attract a wide clientele. All diviners, like their neighbors, engage in farming and participate fully in village life.

Divination takes many forms, the most common being chicken divination, in which a young fowl is killed and readings are taken from its wings and other features. Sacrifices and libations, along with initiation into a spirit-possession or other society, may result from a divinatory séance. Divination and subsequent rituals may divide people, especially if witchcraft is diagnosed, but in many contexts the systern allows villagers to express their solidarity with each other without loss of individual identity. In addition to ritual focused upon individuals and attended by their kin and neighbors, there is some public ceremonial at village and wider levels. Chiefly rituals are still sometimes performed, and there are ceremonies to cleanse a village of pollution when a member dies.

Representational art is not strongly developed; it has mainly ritual functions. Music and dancing are the main art forms, and drums are the main instruments, although the nailpiano (a box with metal prongs that twang at different pitches) and other instruments are also found. Traditional songs are sung at weddings and at dances, but new songs are also composed by dance leaders. Male dance teams are the most common, but some female and mixed teams perform. Ritual and other societies have their own dance styles. Transistor radios are now widespread. Local and visiting jazz and other bands play in the towns.

Diviners and other local experts provide herbal and other forms of treatment for illness. Shops sell some Western medicines, including aspirin and liniments. Village dispensaries and state and mission hospitals also provide Western medicine. People commonly use both Western and indigenous treatments rather than trusting wholly in either.

The Sukuma are one of many ethnic groups who use animals in their traditional medicine, also known as "zootherapy." Like other African groups including the Swaziland Inyangas and Bight of Benin, many believe that traditional medicines derived from animals are more effective than Western-style medicine. Plants and animals have been the basis for Sukuma medicine for centuries; however, nowadays plant medicines are used more. The Sukuma people use a system of naming that allows them to distinguish animals according to their medical purposes. Healers organize faunal medicines by first taking a list of known diseases and their symptoms, then making another list of plants, animals, and their healing properties.

Within the communities, healers are the ones who direct what and how each animal will be used. For example, pangolins are believed to be a sign for a good harvest year, so healers will sell pangolin scales to protect crops. Because snakes and porcupines are a danger to people and crops in Sukumaland, medicine men and healers captured them to be used as entertainment.

There is little information on the Sukuma tribes' use of animals in their medicine because most of the research that has been done on the medicinal practices of this tribe has been plant based. A study was conducted in the Busega District of Tanzania, an area comprising the Serengeti Game Reserve and Lake Victoria, to determine which faunal resources healers use to treat illnesses within the community. Many of the traditional medicines, referred to as dawa, are no longer practiced, as many Sukuma tribe members rely more on Western-style medicine.

The biggest threat to conservation in Tanzania is the legal and illegal trafficking of wild animals for pets. There are also weak policies for regulating the census of endangered animals. Traditional healers do not pose as big of a threat to conservation efforts as commercial hunters do. Unlike the latter group, traditional hunters and medicine men only hunt what they need. Other than medicinal purposes, the Sukuma people use animal resources for things such as decoration and clothing. For example, animal skins are used for house decoration and bags.

Funerals are important rituals for bereaved families and their kin and neighbors. Neighbors dig the grave and take news of the death to relatives of the deceased who live outside the village. The dead become ancestors who may continue to affect the lives of their descendants and demand appeasement. The idea that the dead live on in their descendants is expressed in terms of shared identity between alternate generations.

Relationships between the Sukuma and their non-Nyamwezi neighbors, the Tatoga, were generally good and they did not regard each other as enemies, as they were mutually dependent on one another. The Tatoga needed the grain of the Sukuma while the Sukuma needed the cattle and the highly regarded rainmaking diviners of the Tatoga (the Tatoga were considered the very best at this important and highly specialized activity). The Maasai, however, were considered enemies. The Tatoga–Sukuma relationship was centered on cultural and economic exchange, while the Sukuma–Maasai connection was centered on fear and hatred, for cattle were the only thing the Maasai wanted from the Sukuma, believing that God had granted the Maasai all the cattle in the world. However, it is still possible that some peaceful relationships did exist. The Sukuma were very selective in what they assimilated, just as the Nyamwezi were; they were able to assimilate others but were unable to assimilate themselves into other societies. One Sukuma myth states that the Tatoga (Taturu) were their leaders and chiefs when they migrated from the north; the Taturu were the cattle herders and needed open plains for their cattle and moved into the greater Serengeti area. The Sukuma were left closer to the big Nyanza (Lake Victoria), cleared the forests and became the agriculturalists. Even then, when the Taturu moved out toward the plains, they left Taturu administrators to "rule" over the Sukuma. For this reason, up until the time of the dissolution of the chieftain system, all chiefs and major headmen represented themselves as Taturu even though they were now within the Sukuma area.

The Nyamwezi (also called Wadakama, or people of the South and Sukuma (also called people of the North) are two closely related ethnic groups that live principally in the region to the south of Lake Victoria in west-central Tanzania. When using ethnic names, they describe themselves as "Banyamwezi" (sing. Munyamwezi) and "Basukuma" (sing. Musukuma) respectively; they refer to their home areas as "Bunyamwezi" or "Unyamwezi," and as "Busukuma." The term "Sukumaland" is sometimes used for the Sukuma area. The name "Sukuma" literally means "north," but it has become a term of ethnic identification.

The Nyamwezi and Sukuma region lies between 2°10′ and 6°20′ S and 31°00′ and 35°00′ E. The Nyamwezi "home" area is in the Tabora Region and western Shinyanga Region, and Sukumaland lies to the north and east, covering the eastern Shinyanga Region and the Mwanza Region. There has been much population movement in and beyond these areas, and members of both groups have also settled on the coast and elsewhere. Sukuma and members of other groups, such as the Tutsi and the Sumbwa, are often found in Nyamwezi villages, but Sukuma villages are ethnically more homogeneous. Sukuma took over the Geita area of Mwanza Region during the colonial period, and they have expanded farther west since then. They have also moved down into Nzega District and the neighboring Igunga District, and some have migrated into the southern highland areas of Tanzania, and even into Zambia. These Sukuma movements have stemmed from political factors, such as colonial cattle-culling policies, and from local overcrowding and deteriorating soil conditions. The two areas form a large and undulating tableland, most of it at elevations between 1,150 and 1,275 metres (3,773 and 4,183 ft). There are several rivers in the region, but most of them do not flow during the drier months. The year can be broadly divided into a rainy season, from about November until April, and a dry season the rest of the year. Average annual rainfall is about 75 centimetres (30 in) for most of the Sukuma area, and about 90 centimetres (35 in) for Unyamwezi, but there is much variation from year to year and from place to place. Across the region, there is a regular sequence of soil and vegetation zones. The upper levels are dry woodland typified by trees of the Brachystegia-Isoberlinia association; these areas are often called miombo country, after one of these trees. Lower areas of grass and thornbush steppe are also common, and in Sukumaland there are large tracts of park steppe interspersed with baobabs.

Sources: