The Hamar (also spelled Hamer) are an Omotic community inhabiting southwestern Ethiopia. They live in Hamer woreda (or district), a fertile part of the Omo River valley, in the Debub Omo Zone of the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNPR). They are largely pastoralists, so their culture places a high value on cattle. PopulationThe 2003 national census reported 46,532 people in this ethnic group, of whom 10000 were urban inhabitants. The vast majority (99.13%) live in the SNNPR. According to the Ethiopian national census of 1994, there were 42,838 Hamer language speakers, and 42,448 self-identified Hamer people, representing approximately 0.1% of the total Ethiopian population. LanguageHamer-Banna. 42,838 Hammer language speakers |

|

Banna are their meighbours.

Relations with neighbouring tribes vary. Cattle raids and counter-raids are a constant danger. The Hamar only marry members of their own tribe, but they have nothing against borrowing – songs, hairstyles, even names – from other tribes in the valley like the Nyangatom and the Dassanech

Mingi, in the religion of the Hamar and related tribes, is the state of being impure or "ritually polluted". A person, often a child, who was considered mingi is killed by forced permanent separation from the tribe by being left alone in the jungle or by drowning in the river.

Tthey believe that natural objects (rocks, trees, etc.) have spirits. They also believe in jinns, or spiritsthat are capable of assuming human or animal form and exercising supernatural influence over people.

The Hamer live in camps that consist of several related families. The families live in tents arranged in a circle, and the cattleare brought into the center of the camp at night. When the campsite is being set up, beds for the women and young children are built first; then the tent frame is built around it. The tents are constructed with flexible poles set in the ground in a circular pattern. The poles are bent upward, joining at the top, then tied. The structures are covered with thatch during the dry season and canvas mats during the rainy season. Men and boys usually sleep on cots in the center of the camp, near the cattle. Herds belonging to the Hamer-Banna consist mainly of cattle, although there are some sheep and goats. Camels are used for riding and as pack animals.

Most Hamer-Banna plant fields of sorghum at the beginning of the rainy season before leaving on their annual nomadic journey. Some households also plant sesame and beans. Because the crops are usually leftunattended, the yields are low. Few households grow enough grain to last through the year.

Honey collection is their major activity and their cattle is the meaning of their life. They will stay for a few months wherever there is enough grass for grazing, putting up their round huts. When the grass is finished, they will move on to new pasture grounds. This is the way they have been living for generations.Once they hunted, but the wild pigs and small antelope have almost disappeared from the lands in which they live; and until 20 years ago, all ploughing was done by hand with digging sticks.

The land isn’t owned by individuals; it’s free for cultivation and grazing, just as fruit and berries are free for whoever collects them. The Hamar move on when the land is exhausted or overwhelmed by weeds.

Often families will pool their livestock and labour to herd their cattle together. In the dry season, whole families go to live in grazing camps with their herds, where they survive on milk and blood from the cattle. Just as for the other tribes in the valley, cattle and goats are at the heart of Hamar life. They provide the cornerstone of a household's livelihood; it’s only with cattle and goats to pay as ‘bride wealth’ that a man can marry. A lot of their culture has now become well-known to the outside world. It's a real privilege to get to know them.

There is a division of labour in terms of sex and age. The women and girls grow crops (the staple is sorghum, alongside beans, maize and pumpkins). They’re also responsible for collecting water, doing the cooking and looking after the children - who start helping the family by herding the goats from around the age of eight. The young men of the village work the crops, defend the herds or go off raiding for livestock from other tribes, while adult men herd the cattle, plough with oxen and raise beehives in acacia trees.

Sometimes, for a task like raising a new roof or getting the harvest in, a woman will invite her neighbours to join her in a work party in return for beer or a meal of goat, specially slaughtered to feed them.

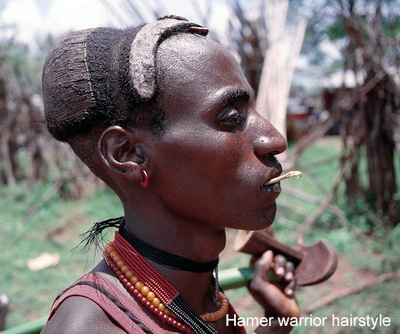

One striking characteristic of the Hamer-Banna men and women is that they indulge in elaborate hair-dressing. They wear a clay "cap" that is painted and decorated with feathers and other ornaments. Much time is spent inpreparing the hair, and care must be taken to protect it from damage. This is one reason the men often sleep on small, cushioned stools. The women use the butter for the perfect look manteinance of their hair-dressing. A well-dressed man will wear a toga-like cloth and carry a spear and a stool. Women also commonly wear colorful toga-like garments. Men may marry as many women as they like, but only within their own ethnicity. A "bride price" of cattle and other goods is provided by the prospectivehusband and his near relatives. A typical household consists of a woman, her children, and a male protector. A man may be the protector of more than one household, depending on the number of wives he has.

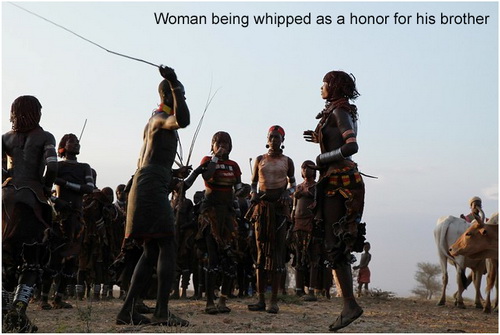

FamilyHamar parents have a lot of control over their sons, who herd the cattle and goats for the family. It’s the parents who give permission for the men to marry, and many don’t get married until their mid-thirties. Girls, on the other hand, tend to marry at about 17. Culture and traditionsThe maza are also responsible for a ritual whipping which precedes the main cattle jump. The village's women purposefully provoke the maza into lashing their bare backs with sticks which inflict raw, open wounds and scar them for life. However, these wounds are seen as the mark of a true Hamar woman, and the pain is worn with honor. Because the sister or relative was whipped at the man's ceremony and endured the pain for him she can later in life look to him for help if she falls on hard times because she has the scars from the whipping she received for him to prove his debt to her. Women commonly end up as the heads of families because they marry men who are much older than themselves while they are young. When her husband dies she is left in control of the family's affairs and livestock. She is also in control of his younger brothers and their livestock if their parents are dead. Widows may not re-marry. Also, men are sometimes assigned the responsibility of protecting a divorced woman, a widow, or the wife of an absent husband (usually his brother). Marriage celebrations include feasting and dancing. Young girls as well as boys are circumcised. Women know many ways to do their hair. The most famous hair style is when their hair is in short tufts rolled in ochre and fat or in long twisted strands. These coppery coloured strands are called "goscha", it's a sign of health and welfare. Some woman have three necklaces. According to what I just explained about the bignere, the biggest one at the top means she was "First Wife". This is important, as her status is the higher one in Hamer society. But as she has two more simple necklaces around her neck: that means her husband took two more wives... The Hamar women who are not first wife have a really hard life and they are more slaves than wives... During my trip, I could see some of these women, working like slaves for the men: their skin were covered with clay, butter and animal fat... So they were a little scary ! Another thing to know about these women: the more scars one has on her back, the higher is her status. The young unmarried girls, for their part, wear a kind of oval shape plate, in metal. It is used like a sunshield, but it tends to be rare in the tribe. Some of them have fund their future husband, but have to wait in their house until the so-called pretender can provide all the money for the ceremony: he has to pay for all the cows the bride-to-be's family asks for. These girls are called "Uta" and have to wait three months, entirely covered with red clay... And no right to take baths or showers ! They cannot go out of the house, let alone the village.That's why it is very rare to see or take a photo of a Uta A cruel tradition still has currency for some Hamar: unmarried women can have babies to test their fertility, but some of them are just abandoned in the bush. This tradition tends to disappear but NGO still save abandoned new borns. Abandonment are all the more frequent than some Hamar believe that a child born out of formal marriages has "mingi", as to say something abnormal and unclean. For them, it is the expression of the devil, which may cause disasters such as epidemics or drought in the village. So, illegitimate children are abandoned. This kind of beliefs can also be observed in other Ethiopan tribes: many parents prefer to sacrifice their own child rather than risk being affected by the evil eye. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bull-Leaping ceremonyThe Hamar have very unique rituals such as a bull-leaping ceremony, that a young men has to succeed in order to get married. A Hamar man comes of age by leaping over a line of cattle as an initiation rite of passage. It’s the ceremony which qualifies him to marry, own cattle and have children. The timing of the ceremony is up to the man’s parents and happens after harvest. As an invitation, the guests receive a strip of bark with a number of knots – one to cut off for each day that passes in the run up to the ceremony. Cows are lined up in a row. The initiate, naked, has to leap on the back of the first cow, then from one bull to another, until he finally reaches the end of the row. He must not fall of the row and must repeat successfully the test four times to have the right to become a husband. While the boys walk on cows, Hamar women accompany him: they jump and sing. They have several days of feasting and drinking sorghum beer inprospect. On the afternoon of the leap, the man’s female relatives demand to be whipped as part of the ceremony. The girls go out to meet the Maza, the ones who will whip them – a group of men who have already leapt across the cattle, and live apart from the rest of the tribe, moving from ceremony to ceremony. The whipping appears to be consensual; the girls gather round and beg to be whipped on their backs. They don’t show the pain they must feel and they say they’re proud of the scars. They would look down on a woman who refuses to join in, but young girls are discouraged from getting whipped. One effect of this ritual whipping is to create a strong debt between the young man and his sisters. If they face hard times in the future, he’ll remember them because of the pain they went through at his initiation. Her scars are a mark of how she suffered for her brother. As for the young man leaping over the cattle, before the ceremony his head is partially shaved, he is rubbed with sand to wash away his sins, and smeared with dung to give him strength. Finally, strips of tree bark are strapped round his body in a cross, as a form of spiritual protection. Meanwhile, the Maza and elders line up about 15 cows and castrated male cattle, which represent the women and children of the tribe. The cattle in turn are smeared with dung to make them slippery. To come of age, the man must leap across the line four times. If he falls it is a shame, but he can try again. If he is blind or lame he will be helped across the cattle by others. Only when he has been through this initiation rite can he marry the wife chosen for him by his parents, and start to build up his own herd. Once his marriage has been agreed upon he and his family are indebted to his wife's family for marriage payments amounting to 30 goats and 20 cattle. At the end of the leap, he is blessed and sent off with the Maza who shave his head and make him one of their number. His kinsmen and neighbours decamp for a huge dance. It’s also a chance for large-scale flirting. The girls get to choose who they want to dance with and indicate their chosen partner by kicking him on the leg. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: